This term I’ve been doing a course on probabilistic model theory, and as part of that I’ve had to think a lot about Markov chains recently. This has been surprisingly fun, and here I’d like to talk about one of the problems that we can solve with Markov chains: how do I simulate an $n$-sided die using just coin flips?

Knuth and Yao [1] give an answer to this question, and in particular provide a framework for how to understand the complexity of random number generation more generally (hence the title of the paper). The way to do it can already be found elsewhere online, so no new results are going to be proved here; still, I think it’s a very interesting and pretty result, and so let’s see how to simulate rolling a die by flipping coins.

The six-sided case

Let’s begin with the humble six-sided die. How can we simulate it if all we have is a (perfectly unbiased) coin? Well, as suggested by Knuth and Yao, we can flip the coin three times. If we get a piece of paper, write down a $\mathtt{1}$ whenever we get a heads and a $\mathtt{0}$ whenever we get a tails, then we get eight possible outcomes of our experiment:

\[ \mathtt{000}, \mathtt{001}, \mathtt{010}, \mathtt{011}, \mathtt{100}, \mathtt{101}, \mathtt{110}, \text{ and } \mathtt{111}. \]

We can then interpret these as binary numbers; easily enough, if we end up with the binary expansion for one of the numbers $1$–$6$, then we’ll assume that that’s the outcome of the die roll we’re trying to simulate. If we come up with a $\mathtt{000}$ or a $\mathtt{111}$, then we throw away this experiment—perhaps we suppose that we accidentally threw the die on the floor and it got lost under the sofa—and start over again, hoping for a sensible outcome this time.

This works! With a bit of thought we can see that we get each of the outcomes $\mathtt{001}$–$\mathtt{110}$ each with probability $1/6$, which is what we’d expect out of a die. One might worry that the above process won’t terminate; for instance, we might roll a $\mathtt{111}$ over and over again ad infinitum. But that happens with probability $0$, as does any non-terminating infinite sequence of tosses, and so we won’t worry about it.

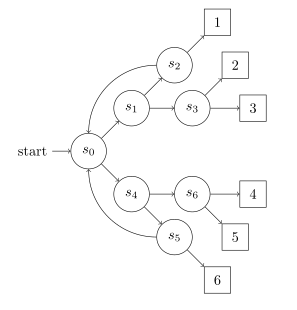

To help visualise this process, we can write it down as a Markov chain. So a Markov chain that simulates a six-sided die roll would be:

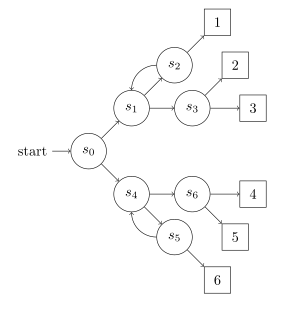

We can do better than this, though; in particular Knuth and Yao provide an algorithm that also simulates a six-sided die, but with a lower expected value for the number of times we’d need to toss the coin. In particular, if we toss a $\mathtt{000}$, then we can interpret the last $\mathtt{0}$ as the first outcome of the next three tosses we do; so we only need to toss two coins instead of three on the next trial. Depicting that as a Markov chain gets us the following:

It’s easy enough to see that this is more efficient than the first Markov chain we saw; we do less repeat work, and so more quickly end up in a final state where we see a die face.

Knuth and Yao then tell us that this is optimal; we can’t find an algorithm that also simulates a six-sided die that’s any better than what we’ve written down here. This is good to know! But to see why that’s the case, we need to think a bit more about what there is that’s special about the probability $1/6$.

Looking at the efficient die example above, we can see that we end up in a die-face state only after $3$ tosses, or $5$ tosses, or $7$ tosses, or so on. Since all transitions in our Markov chain have a probability of $1/2$ of being taken, we can see that we have a probability of $(1/2)^3 + (1/2)^5 + (1/2)^7 + \dots$ of ending up in such a state. That’s how we know that we end up in these states with probability $1/6$; that’s what the infinite sum there adds up to.

But all this summing of powers of $1/2$ looks an awful lot like computing the decimal value of a binary number. The binary expansion of $1/6$ is just $0.0010101\dots$, after all. Notice that the $1$’s appear in the $3\rd$, $5\th$, $7\th$ positions of the binary expansion, and so on, and that in our optimal example we visit a final state only after $3, 5, 7$, transitions, and so on. So it looks like there’s a correspondence between the binary expansion of a fraction $1/n$, and the optimal Markov chain that simulates rolling an $n$-sided die.

But all numbers have binary expansions. So we can generalise the above construction. Let’s do that.

The five-sided case

To start, let’s write down a Markov chain that simulates the rolling of a five-sided die. Don’t try to think too hard about what a five-sided die would look like. All we need to know here is, given a coin, how to model a uniform distribution over $\set{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}$, and we’ll be happy with this as our simulation of a five-sided die.

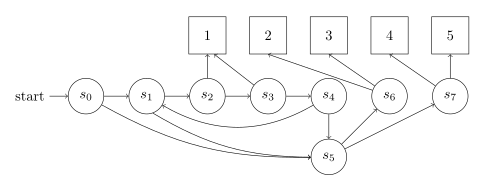

Now, let’s look at the binary expansion of $1/5$. It’s $0.0011001100\dots$. That looks regular enough to capture in a Markov chain; we just need to define a state that’s visited only after $3$ steps, or $4$ steps, or $7$ steps, or $8$ steps, or so on. We can do that.

If we send everything else to another state, then we end up in that state with probability $4/5$. But since we have a coin, we can easily quarter that into four states that we visit each with probability $1/5$; just flip the coin twice to determine the outcome of that roll.

Putting it all together, we get the following Markov chain:

And it works! PRISM (https://www.prismmodelchecker.org/, a tool that lets us probabilistically check models) tells me that, in the above model, we reach each of the die faces with probability $0.2$ (well, with probability $0.19999\dots$, but that’s numerical computation for you). So this method of reading off the binary expansion of a fraction and turning it into a Markov chain really works for simulating die rolls.

The general case

Recall that every number has a binary expansion, and in particular those in $[0,1]$ have binary expansions. It would be nice, then, if we could always create a state in a Markov chain that we end up in, in the long run, with probability $1/ r$, for every real number $r$ between $0$ and $1$. Unfortunately, given that Markov chains are finite, this won’t work. Trying to find a Markov chain where we end up in a state with probability of $1/\pi$ is difficult, given that the binary expansion of $1/\pi$ is the seemingly random $0.0101000101111\dots$. Finding a Markov chain that visits those states after precisely those steps looks challenging.

Indeed, it looks like any Markov chain that does would have to remember where in the binary expansion of $1/\pi$ is; it seems it would need to remember an arbitrary amount of information. But Markov chains (or at least those we can put into computers) are finite; so it seems that there are some esoteric ($\pi$-sided?) dice that we can’t simulate just using coin flips.

More specifically, we can simulate an $r$-sided die, when $r$ is in the interval $[0,1]$, just when $r$ is automatic; in particular I’m taking that to mean that there’s a Büchi automaton that recognises the binary expansion of $r$ (we need to use Büchi automata here, since our binary expansions carry on infinitely to the right). Above, $1/6$ and $1/5$ were automatic, and so we could construct Markov chains that simulated their die-rolls. But $1/\pi$ isn’t automatic, and so we can’t construct a Markov chain that simulates a $\pi$-sided die roll.

At this point, I’ll admit that there’s more I want to know about the connections of number theory to automata theory, and that if you have any good recommendations of what to read on that then do let me know. But it seems like the above could generalise to other radixes, and so we could be able to simulate, say, a $7$-sided die using only flips of a $3$-sided coin (don’t think too hard about what that’d look like either).

In any case, we’ve come across a lot of interesting number theory and automata theory from the original question of how to roll a die using only coins. Knuth and Yao’s paper goes into more detail, so (if you can find it!) it’s certainly worth a read.

Bibliography

- [1] Donald Knuth and Andrew Yao. Algorithms and Complexity: New Directions and Recent Results. 197.